fiction

The Gothic Sublime

Theory of the Gothic Sublime argues that the sublime figures without transcendence: Confronted with the “colossal,” the “absolutely great,” the mind turned inward into its own unconscious, regressed into its own labyrinth, to discover, in the tangled labyrinth of its dreams, a depth from which it could no longer soar into the grand design of the Kantian/Romantic sublime. In the process (of writing out this confrontation) a marked schizophrenic intensity emerges, both at the level of the subject (forever on the verge of madness) and at the level of the signifying chain (there is a distinct radicalization of the relationship between the signifier and the signified, the word and its referent).

Ultimately, however, we are confronted with a kind of black hole theory of the sublime. The black hole, which surfaces in Piranesi’s paintings, “Interiors measurelessly strange, / Where the distrustful thought may range,” or in Mary Shelley’s feverish handwriting, takes us back to the essential problematic of the Gothic and the Postmodern. The problematic takes two forms. The first, articulated so well by Kant, is the issue of the presentation of the unpresentable. Kant, of course, had seen that the representation of the “colossal,” the absolutely great, can occur only at that moment when reason gives way to imagination for a fleeting moment before it regains its power. What happened during this gap, this lapse, this concession or giving way, is the coming into being of the moment of the sublime. The second, articulated by Schopenhauer and Freud, is the “oceanic sublime,” the sublime as the dissolution of self in death. It is the latter, the compulsion toward our own ends (in death), that explains the inherently apocalyptic tendencies in the Gothic as the subject ingratiatingly gets absorbed into the sublime object.

http://graduate.engl.virginia.edu/enec981/Group/zach.sublime2.html

Sublime Horror

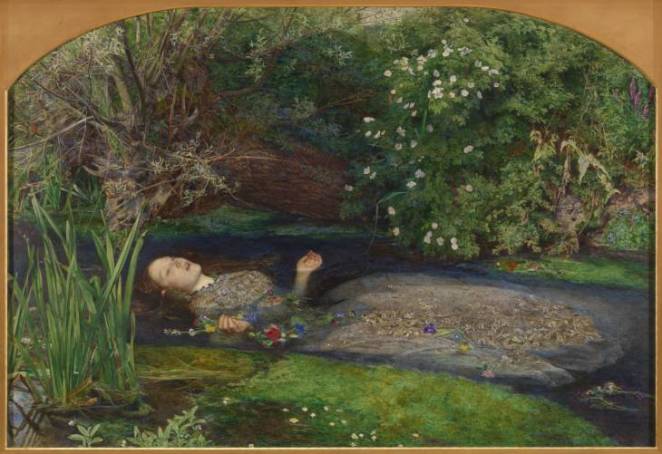

Ophelia – Millais, 1852 Tate

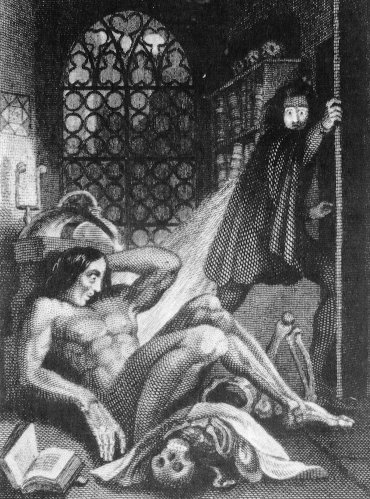

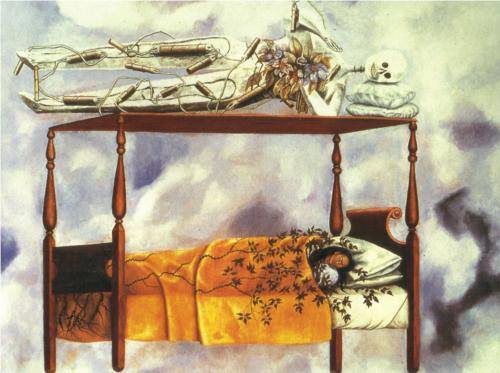

In Kristeva’s Powers of Horror, the abject reflects the human reaction to the threat of breakdown in meaning correlative to the loss of the distinction between subject and object, self and world. Reference to the corpse represents a traumatic loss of identity and functions as the exemplary reminder of our materiality. Mary Shelley’s monster personifies both the corruption of knowledge and power. As an aesthetic representation of the conflation of Science and Nature, Frankenstein is a sublime object. In clinical terms, the monster is an uncanny figure of paranoid knowledge. Millais’ dead object gestures to the uncanny nature of sublime memory; unconsciously, we sense the terrifying knowledge that we already know. Kahlo’s self-portrait represents a form of life-writing that symbolizes the painter’s connection to the natural world. The figure of Death in the image suggests an imaginative network of proleptic meaning on the nature of life experience.